Charles Lindberg will never forget Feb. 23, 1945, the day he stood on the top of Mount Suribachi on the island of Iwo Jima in Japan and helped five of his fellow E-Company members raise the American flag high above the bare, rocky soil. "When the flag was raised, the commotion down below was really something," recalled Lindberg, who was a 24- year-old Marine corporal at the time. "The troops saw the flag up there and they went crazy down there. They hollered and screamed, and the ships out on the ocean picked up the theme and sounded their whistles. It was the first American flag to fly over the Japanese home territory in World War II."

Charles Lindberg will never forget Feb. 23, 1945, the day he stood on the top of Mount Suribachi on the island of Iwo Jima in Japan and helped five of his fellow E-Company members raise the American flag high above the bare, rocky soil. "When the flag was raised, the commotion down below was really something," recalled Lindberg, who was a 24- year-old Marine corporal at the time. "The troops saw the flag up there and they went crazy down there. They hollered and screamed, and the ships out on the ocean picked up the theme and sounded their whistles. It was the first American flag to fly over the Japanese home territory in World War II."

The men remained on top of Mt. Suribachi for just minutes before the sound of enemy shots drew them back into the battle that had started four days earlier, when they'd first landed on Iwo Jima.

Raise it!

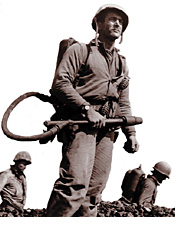

The time between landing on Iwo Jima on Feb. 19, 1945, and raising the flag are days that remain vivid in Lindberg's memory. "It was a rough battle and we took a big casualty on the beach," he said. "Once we finally got off the beach, we cut Mount Suribachi off from the rest of the island. And the 28th regiment, of which I was a member, was given the job to take the mountain.

"It took us from the 19th to the evening of the 22nd just to get to that mountain and we only had a block and a half to go," he recalled. "The Japanese soldiers were underground in caves and big bunkers. And all their caves were interlocked with each other, so they could go from one to the other. And we'd go by and knock out one and they'd come up behind us."

By the evening of Feb. 22, they had the mountain surrounded. "We then heard we were going to start climbing in the morning," Lindberg added, noting they met at Colonel Chandler Johnson's headquarters the next morning. "Johnson, who was the battalion commander, handed Lieutenant Harold Schrier a flag and said ‘If you get to the top, raise it.'"

Surprisingly, the 40 men of the 3rd platoon encountered no opposition as they climbed the mountain. "We couldn't figure it out. Because we'd had so much trouble getting to the mountain, we figured it would be a slaughterhouse on top. But we kept going and going and there was no action — no resistance," Lindberg recalled. Once they climbed all the way to the top, they stationed men out on the rims to guard the area while they began to put up the flag. "Two men found this big pole and brought it back to where we were. And we tied the flag to the pole, carried it to the highest spot we could find — and we raised that flag."

The second flag

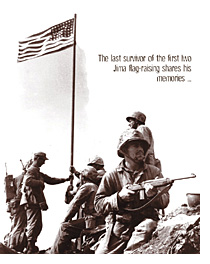

In an odd twist of fate, the Iwo Jima flag-raising would go down in history as one of the more celebrated moments in WWII. Yet the names of the six men who first raised the "Stars and Stripes" to the roar of cheering troops below — Lindberg, Harold Schrier, Earnest Thomas, Henry Hanson, Jim Michels and Louis Charlo, along with photographer Lou Lowery — would become simply a brief footnote to the famous event.

In an odd twist of fate, the Iwo Jima flag-raising would go down in history as one of the more celebrated moments in WWII. Yet the names of the six men who first raised the "Stars and Stripes" to the roar of cheering troops below — Lindberg, Harold Schrier, Earnest Thomas, Henry Hanson, Jim Michels and Louis Charlo, along with photographer Lou Lowery — would become simply a brief footnote to the famous event.

What America and the rest of the world would come to recognize as the flagraising at Iwo Jima took place later that same day, when six other men from Lindberg's Company were ordered to replace the first flag. It was then, after the mountain had been secured, that photographer Joe Rosenthal snapped his now famous photograph of six men triumphantly hoisting the American flag — the photo that graced the covers of newspapers and magazines across the United States, and eventually served as the inspiration for the Iwo Jima monument in Washington, D.C.

After raising the flag and helping to secure the mountain, Lindberg recalled he headed down the mountain at about 1:30 p.m., with the company's other flamethrower, to reload their tanks in preparation for possible assaults during the night. He didn't learn about the second flag until weeks later. "I was gone at the time. Apparently, Colonel Johnson got worried about the flag up there. He was afraid somebody was going to take it for a souvenir and he didn't want anyone to have it, so he ordered it replaced," recalled Lindberg, a retired electrician who resides in Richfield, Minn. "I came back up the mountain at five that afternoon, and nobody said anything about it. We never even paid any attention to it."

Before the battle of Iwo Jima was over, 36 of the 40 men who climbed Mt. Suribachi to raise the first flag were killed or injured. Lindberg was evacuated to Saipan after being wounded on the island's north end on the last day of February. He spent a week or two in the hospital before someone asked him if he was interested in seeing a picture of the Iwo Jima flagraising. "He showed me the picture, and I said ‘Oh, no, no, no, no, that's not the way we did it,'" Lindberg said. "I was looking at Joe Rosenthal's picture."

After being transferred to a hospital in Pearl Harbor a couple of weeks later, Lindberg saw Lou Lowery's photograph of the first flag-raising, in Yank Magazine for the first time, along with the Rosenthal photo.

He later discovered that after Rosenthal had taken the photo, he'd had his film sent to Guam to be developed, then sent back to the United States immediately. "Lou Lowery, the combat photographer who took our pictures, had his film held up for 32 days," said Lindberg, who recalled watching the effects of Rosenthal's photo. "It took the United States by storm. They used it for a war bond drive. They even pulled the last three men alive from the second flagraising out of Iwo Jima and back to the United States for the drive."

Setting the story straight

From that point forward, Lindberg began to encounter resistance when he told people about raising the first flag. "I was called a liar," he said. "People told me, ‘that couldn't have happened.'"

From that point forward, Lindberg began to encounter resistance when he told people about raising the first flag. "I was called a liar," he said. "People told me, ‘that couldn't have happened.'"

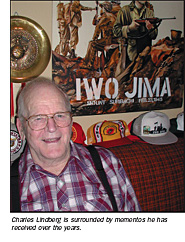

But Lindberg, who received the Silver Star medal for his WWII service, persisted. "I've fought for 50-some years to get recognition for the first flag," said Lindberg. People didn't truly begin to believe him until Lou Lowery sent him copies of photos that documented raising the first flag. Even during the dedication of the Iwo Jima monument, Lindberg, Michaels, Schrier and Lowery, the survivors of the first flag-raising, were relegated to the sidelines while the survivors of the second flag-raising received a great deal of attention. "Since then, I've been all over the United States, talking to people about the first flag," Lindberg added.

Lindberg, who returned to Iwo Jima for the 50th anniversary of the battle and briefly raised a flag again with other Veterans who fought on Iwo Jima, is gratified to realize his efforts at telling America about the first flag-raising have been fairly successful. "Today the story is pretty big," said Lindberg, who has devoted a good portion of his life to telling it. Three monuments to the first flag are being created in his home state, Minnesota, and a Connecticut monument to the second flag also references the first flag-raising.

Today, Lindberg continues to share the story of the first flag. For decades, his goal hasn't changed significantly. "I just want people to know there was a first flag," he said. "That's the main thing."